Earlier I wrote a twitter thread about small things designers can do to make their products more inclusive for trans and non-binary people. It’s a topic quite close to my heart, since I am non-binary myself, so I want to address some of the points in a proper post as well.

As I mentioned in the tweets, there’s more to trans/non-binary inclusive design than what will be discussed in this post, and there’s more to inclusive and ethical design practices than just gender issues. This will be an overview of things that can be done at relatively small cost, but will have a positive impact for gender diverse people.

But let’s first take a closer look at what it actually means to be non-binary. In short, non-binary is an umbrella term for genders that fall outside of the male/female gender binary. This includes several things, such as having no gender, multiple genders, a gender different than or between male and female, and culturally specific genders (such as two-spirit).

A lot of us use gender neutral pronouns (such as they/them), but it’s also common and perfectly valid for non-binary people to use binary pronouns (he or she), neopronouns, or a combination of different pronouns.

In my case, being non-binary means I am neither a man nor a woman, and exclusively use gender neutral pronouns (singular they/them).

I will include more resources explaining non-binary identities at the bottom of this post. For now, let’s get back to the topic of non-binary inclusive design.

Forms and data collection

Forms and surveys, both physical and digital ones, are notorious for excluding non-binary people.

Most often, they only have two gender options: male or female. Always presented as radio buttons or drop down menus, meaning only one gender can be chosen, and usually made obligatory, meaning a choice has to be made.

As a non-binary person, there’s no good outcome for me there. Either I lie and misgender myself as a woman, or I lie and misgender myself as a man.

Gender options on the Tinder iOS app. We want to find friendships or love that accept and respect our identities, but there’s no option for non-binary people to specify our gender. We have to list ourselves as a man or as a woman. Either way, we’re misrepresented from the start, opening the door for misgendering, harassment and abuse later on.

Fortunately, some forms do include a third option. Unfortunately, that third option is often “Rather not say”. I would very much like to say my gender, it’s just not possible.

Another option that’s often used is “Other”. While I assume that one exists because of the combination of good intentions (making sure people who fall outside the gender binary can answer) and technical limitations (both internationalization and limiting the amount of possible responses), it can easily come across as dehumanizing.

Society already emphasizes a lot that we’re different, falling outside the norms of binary cis women and men, so having to label ourselves as “other” online as well can feel rather damaging.

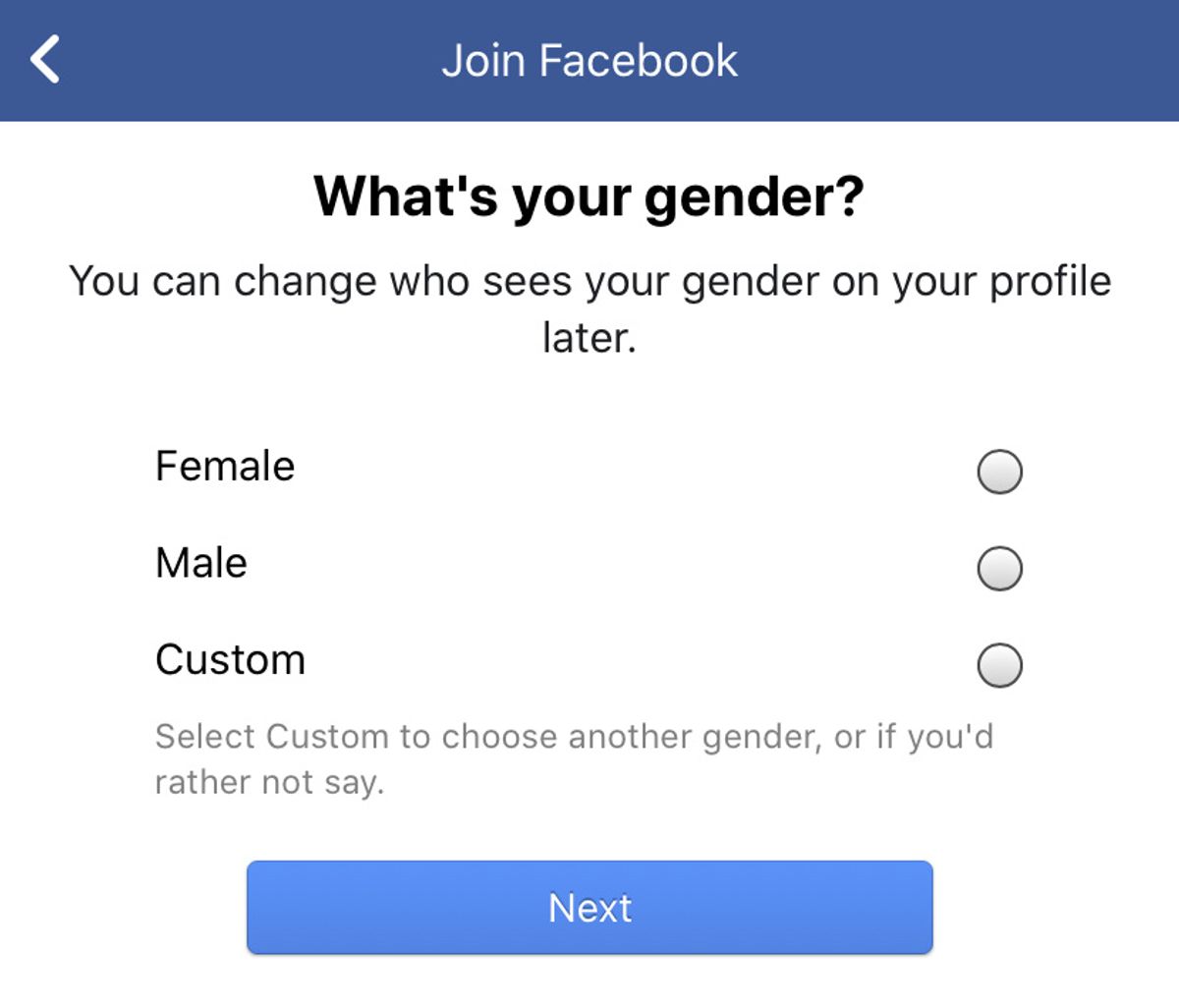

The three genders according to Facebook: Female, Male, Custom.

A similar situation over at Gmail. After choosing a “custom” gender, I had to choose whether my pronouns were male or female (gendering pronouns for someone who doesn’t gender themself feels wrong too; better would be to show an example), or other. There’s no information if “other” in this context means they/them, and there’s also no opportunity to actually write down my pronouns myself instead.

A better way would be to include a lot more gender options along with a “write in” or “not listed here” open text field. By calling the missing options “not listed”, the responsibility is also put on the designer/platform (they didn’t list us), rather than on the people filling in the form (we’re too “other”).

Another option is to just go for an open text field from the start, and make everyone write down their gender. Autocomplete suggestions can be used to discourage spelling mistakes, and with some post-processing of the data similar answers (eg “female”, “woman”, “women”, “womxn”) can be grouped as well.

Additionally, when offering different options, it’s also wise to consider going for checkboxes, rather than radio buttons or drop downs, allowing people to select several genders, rather than the one they most identify with.

But the way gender is asked for on forms doesn’t just exclude or harm non-binary folks, often the issues extend to binary trans people as well.

The following example comes from an article from 2016 about how to ask for gender in surveys, but is one I’ve come across in the wild on products as well.

By putting “female” and “transgender female” against each other, it’s implied that trans women aren’t real women (and same for trans men), or at the very least that they’re not “normal” women and men.

There’s not many instances where you’ll need to specifically know whether someone is a trans man or a cis man, for example. If you’re creating an interface for a doctor’s office, it might be useful for the doctor to know in order to call in their patients for the correct examinations.

Another example of where it could be useful to ask, is when collecting demographics data for research where the differences in answers between trans and cis people might be important (for example, a survey about online harassment).

In those cases, the example above could be adapted to:

- Cis woman

- Cis man

- Trans woman

- Trans man

- ...

Or alternatively, whether the respondent is cis or trans can be a follow-up question.

Do you even need to know gender?

The best way of avoiding most of these issues is by not asking for gender (or pronouns, or title) if you don’t actually need to known them for a specific and valid reason. For example Instagram uses they/them for everyone by default.

If you do need to ask, start by answering the following questions for yourself: why do you need to know this data, and how is it going to be used?

This will usually give you some more insights in what exactly you should ask the user, and which format the input should have. Gender and pronouns are not interchangeable - for example, as I mentioned earlier, not all non-binary people use they/them pronouns. Trans people their gender doesn’t match their gender assigned at birth. Gender and chromosomes/body parts aren’t interchangeable either.

Be specific, ask only what you need to know, and explain what the data will be used for.

Allowing for change

Gender, pronouns, titels and names might change over time, and it’s important to keep this in mind when designing and developing products.

When I changed my last name in 2019, I experienced first hand how difficult or even impossible it is to update my name in some systems. We use Jira at work, and despite having changed my name what feels like a million times in their settings, my old name I initially signed up with keeps being displayed.

And because it’s taking a while to receive an updated passport, there are still some services where I cannot sign up using my new legal name, but also cannot make or receive payments because my username doesn’t match my legal name, causing an administrative nightmare.

I also heard from trans people who, for a long time after changing their name in their account settings on Netflix, kept receiving promotional emails using their old name.

One form can cause a lot of harm

The examples above, and non-inclusive forms in general, can cause harm in several ways.

First of all, whether it’s non-binary people not having an option, or trans women not being classified as women, people end up being excluded and demonized. We’re either not represented at all, misrepresented, or invalidated.

In the Tinder example, where non-binary people might be shown as a wrong gender to potential new partners, the platform also puts all responsibility on its non-binary users to come out to their new matches, correct their pronouns and explain their identity. It’s tiring to constantly have to correct and educate those around us. Tinder had a good opportunity to take some of that burden away from us, but chose not to.

But in the age of big data, there’s more risks attached to misrepresentation in forms. The data we collect gets used and analyzed, and often fed into algorithms. Broken data leads to broken algorithms. And an entire group being erased from data collection leads to an entire group being erased from its analysis. Non-binary people are already invisible enough in society, forgotten about, underrepresented or not recognized as a real and valid identity. Our voices shouldn’t be erased even more.

A good example of this is a survey I had to take at some point in my career. The company I worked for at the time wanted to poll how we were doing, and what we thought about our work culture. The first question, obligatory to answer, was asking about our gender. There were only two options to choose from, male and female.

Further on we were asked if we thought the company was a safe place for queer people (sidenote, we were not asked about our sexuality either), and if we experienced discrimination based on our gender identity.

My answer, along with the answers of other non-binary employees, blended in together with those of men and women. Later on, both the external company conducting the survey and internal management patted themselves on the back: the company received a near top-score for gender equality, and almost no one reported feeling unwelcome because of their gender or sexuality.

Except with the majority of the company being cis and straight, and the answers of queer people not being represented correctly, an “almost perfect score” sounds a lot less perfect. How can they know that non-binary people experience harassment if they don’t even give us a proper voice?

Language matters

Being a non-binary person in tech, I often am wrongly put on “women in tech to follow” lists. While it’s a nice sentiment, who doesn’t like some validation for their work, it puts us in an uncomfortable position. First of all, because I’m not a woman. It’s misgendering me. But pointing that out, no matter how politely, also opens the door to a lot of (verbal) abuse.

And similarly, a lot of events and communities try to show they’re inclusive by saying they’re open for “women and non-binary people”.

For non-binary people like me, it feels bad to always be grouped together with women, especially because I often get misgendered as one. So to me, it’s never clear whether people will actually welcome me for who I am, a non-binary person who’s neither a man nor a woman, and respect my identity, or if they will look at me as a woman or a “woman-lite”.

And for some non-binary women the division between “women” and “non-binary people” can be experienced as harmful as well.

So while the intention behind “women and non-binary people” might*** be good, the language can actually end up excluding more people than includes, and create unsafe and unwelcoming spaces.

*sometimes it’s also just a meaningless phrase to seem more inclusive without having to put in the work.

The same goes for language used when advertising products. “Menstrual products” is more inclusive than “feminine hygiene”, similar to how “people who menstruate” in context is more inclusive than “women”; because not all women menstruate and not all those who menstruate are women.

Representation, harassment, discrimination and a lot more.

In this post I only highlighted a few challenges and and possible solutions. Non-binary and trans people are still underrepresented, both in the design and tech industry, in our research, and in the content published on our platforms. We‘re underpaid, discriminated against and face harassment. Just the other day I had to block someone on Twitter for harassing me and a non-binary friend of mine about our identity.

There’s a lot more to dive into in follow-up posts, but until then I suggest checking out the following resources:

- Trans inclusive design

- Non-binary definition

- Transgender definition

- Non-binary identities in the research community

- 10 Ways to be a better ally to non-binary people

- This is what non-binary people look like

- Designing products for gender inclusion

- Marginalized by design

- http://pronoun.is

- Why is it "pronouns" and not "preferred pronouns"

- Why is it "they are non-binary" and not "they identify as non-binary"

- Things not to say to a trans person

- Non-binary awareness week on Twitter

- What does it mean to be non-binary (via Twitter)

International Non-Binary Day and Non-Binary Awareness Week

I’d also like to end this post on a positive note. While navigating the internet as a non-binary person brings up uncomfortable, painful and sometimes abusive situations, the internet has been a massive help for me as well to help me come to terms with my gender identity.

There’s a lot of information out there, hashtags that are meant to raise awareness and uplift non-binary voices, and even an entire community of queer designers and transgender and gender diverse people in tech.

And as I’m writing this post, it’s International Non-Binary People’s Day, as a part of Non-Binary Awareness Week. It’s great to see effort being put into raising awareness and visibility, and I’m really damn proud to be non-binary.

Hi! 👋🏻 I'm Sarah, a self-employed accessibility specialist/advocate, front-end developer, and inclusive designer, located in Norway.

I help companies build accessibile and inclusive products, through accessibility reviews/audits, training and advisory sessions, and also provide front-end consulting.

You might have come across my photorealistic CSS drawings, my work around dataviz accessibility, or my bird photography. To stay up-to-date with my latest writing, you can follow me on mastodon or subscribe to my RSS feed.

💌 Have a freelance project for me or want to book me for a talk?

Contact me through collab@fossheim.io.

Similar posts

Wednesday, 29. July 2020

Thoughts on Genderify, gender discrimination, transphobia, and (un)ethical AI.

Monday, 8. March 2021